CHAPTER XVII

The Prussian retreat – The English fall back upon Waterloo – Affair at Genappe – The Night before Waterloo

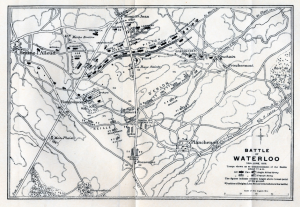

NAPLOEON’S victory at Ligny having caused Marshal Blücher to retire with his army, the Duke was obliged to make a retrograde movement on Waterloo, in order to keep in touch with the Prussians. Selecting a position on which he could rely on Blücher’s co-operation from Wavre, Wellington issued his orders for the allied army to be drawn up in front of Mont St. Jean at the junction of the Charleroi and Nivelles roads leading to Brussels.

Marshal Ney, perceiving the British in retreat, at once pushed forward his cavalry. Thereupon Vivian moved the Tenth Hussars across the slope above the Namur road, and there posted them in echelon of squadrons. At that moment Wellington with his staff rode up and halted in front of the Regiment, and it was from this point that the Duke soon afterwards saw the advance of the enemy’s cuirassiers, preceded by lancers. Scouting parties from the 10th and 18th Hussars were sent out, but being unable to check the French advance, the piquets fell back, and the Tenth Hussars took up their proper position in the line. Then Vivian, forming in a new alignment, threw back his left, so as to present a front to the enemy, and also to protect the left of the whole line. Vandeleur’s brigade was during this movement in the right rear of Vivian’s and close to Quatre Bras.

As soon as Wellington discerned Ney’s intention to molest his retreat, it became a question of deep consideration whether it would be advisable to offer a serious resistance to the enemy’s advance. When, however, Lord Uxbridge made the remark that the defiles in rear as well as the distance of the allied infantry would prevent their co-operation, the Duke, without hesitation, ordered the cavalry to continue their retreat. To carry this into effect the Earl of Uxbridge immediately formed his cavalry into three columns, and retired in the following order: – The right column, consisting of Grant’s and Dornberg’s light cavalry brigades, by the ford a little above the town of Ganappe; the centre column, composed of all the heavy cavalry, along the Brussels highroad; and the left column formed of Vandeleur’s and Vivian’s brigades, across the bridge over the river Ganappe at Thuy.[1]

Scarcely had these disposition been made than the piquet of the 18th Hussars was driven in by two or three squadrons of French cavalry. Vivian, however, opened fire with his battery of Horse Artillery, and checked their further advance. The French then hastily brought up their artillery and fired upon the Hussars brigade. But Vivian, who had received instructions from Lord Uxbridge to retire, coupled with an intimation that he would be supported by Vandeleur, then in his rear, perceived the enemy’s cavalry pressing forward in great numbers, not only in his front, but also on his left flank, put his brigade about and retired in line, covered by skirmishers. On nearing Vandeleur’s brigade, Vivian was surprised to find the second line also in retreat; for he had expected to retire through the intervals of that brigade, and was not aware of the instructions given to Vandeleur “to leave the road clear”. He immediately occupied the ground thus vacated, and ordered the 18th to charge the French as soon as they came within reach. “It was now that a violent storm of thunder and rain broke over the field of battle. The 18th Hussars were just preparing to charge, and only waiting until the guns of the brigade had created disorder in the enemy’s ranks. At the first discharge of artillery the heavens burst forth with peals of thunder, and poured down torrents of rain.”[2] In a few minutes the ground became so saturated with water that rapid movements of cavalry were impracticable. In consequence of this state of the ground Vivian determined to retire onto the Brussels road. He dispatched at once his battery of Horse Artillery towards the bridge over the Genappe at Thuy, and sent an Aide-de-Camp to request Vandeleur to move his brigade across with all rapidity, so as to leave the bridge clear for the passage of his guns and cavalry. The enemy still closely followed the left column, and, as there was some difficulty in passing the squadrons over the bridge, Vivian ordered a portion of the Tenth hussars to dismount as soon as they had reached the opposite bank of the river, and there be prepared with their carbines to defend the passage of the remainder of the brigade, should their retreat be hardly pressed. So bold, however, was the enemy’s attack that a squadron of the First German Hussars was cut off from the bridge and compelled to pass the Genappe at a point lower down the stream. Meanwhile, having ascertained that all was ready, Vivian galloped over the bridge with the remainder of the 1st German Hussars, followed by the French loudly cheering; but the fire from the dismounted men of the Tenth, together with the site of the remainder of the regiment and the whole of the 18th Hussars formed up on the rising ground beyond, checked the pursuit. After remaining in this position for some little time, Vivian’s brigade continued its retreat without further molestation along a narrow cross-road leading through the villages of Glabois, Frischermont, Smohain, and Verd-Cocou.[3]

While Vivian fell back with his brigade, the 7th Hussars were left in Genappe to check the pursuit, and were hotly engaged with the enemy in covering the retirement of the army. Wellington, at the same time fell back with the whole of his troops towards the forest of Soignies, where he took up a position on either side of the high road from Charleroi to Brussels at Mont St. Jean, in front of the village of Waterloo. Napoleon followed with the great bulk of his forces, and formed them nearly opposite to the English on both sides of the same high road, with his headquarters at La Belle Alliance. Thirty-two thousand French under Grouchy were detached to observe the Prussians retiring on Wavre, while the numbers remaining with Napoleon himself were about 72,000,[4] with 248 guns. Wellington’s forces numbered about 68,000[5] strong, with 156 pieces of artillery. Included in this total were nearly 16,000 cavalry on the French side, and between 12,000 and 13,000 on that of the Allies.[6]

“Never was a more melancholy night passed by soldiers than that which followed the halt of the two armies in their respective positions on the evening of the 17th. The whole day had been wet and cloudy, but towards evening the rain fell in torrents.”[7] The two armies bivouacked in their respective positions, the space between them in some places not exceeding 1,500 yards. In the early morning the vedettes of the opposing sides might be seen withdrawing, while the drying and cleaning of firearms became general, and soon the troops on each side were moved to the several points assigned to them.

CHAPTER XVIII

The Field of Waterloo – Positions of the Cavalry Brigades – Commencement of the Battle – Charges of Somerset’s and Ponsonby’s Brigades – Vandeleur’s and Vivian’s Brigades Take Ground to the Right

THE Selection of the ground on which battle was to be given to such a formidable opponent was carefully made by Wellington. Although the choice was in every respect limited, the duke displayed the skill, judgement and forethought for which he was always so pre-eminently distinguished in determining the British position at Waterloo. Several conditions had to be taken into consideration. Firstly, the Prussians posted at Wavre, ten miles off, ought to have facility in affording timely aid to the British; secondly the ground ought not to be favourable to cavalry and artillery, in which arms the enemy was greatly superior; and lastly, the position must afford shelter to the new and hastily combined elements of the Allied army, so as not to expose them unnecessarily at the commencement of an engagement. Yet all these conditions were fulfilled. Moreover, the right flank, resting on the village of Merbe-Braine, was well secured by a ravine; whilst the left flank was protected by the hamlets of La Haye and Papelotte. In front of the right was the now historical farmhouse of Hougoumont and in advance of the centre the scarcely less famous buildings of La Haye Sainte.

The incidents of this great and decisive battle, which replaced the legitimate sovereign of the throne of France and restored tranquillity to Europe, are generally so well known that it will only be necessary here to allude to movements of other corps when they form a connecting link to the operations of the one regiment especially dealt with in these matters.

To render the cavalry actions intelligible, a brief account must here be given of the places occupied by the brigades in the line of battle. The Allied cavalry, consisting of seven brigades of British and King’s German Legion (8,373 men strong), Hanoverian and Brunswick (2,604 strong), and Dutch-Belgian (3,505 strong), was under Lord Uxbridge. These brigades, formed by regiments mostly in close columns of squadrons at deploying intervals, were posted on the reverse slopes of the main ridge or hollows screened from the enemy. On the extreme right, near to the Nivelles road, stood the 5th Brigade, consisting of the 7th and 25th Hussars and 13th Light Dragoons, under Major-General Sir Colquhoun Grant. On his left was the Third Brigade, under Major-General Sir William Dornberg, consisting of the 23rd Light Dragoons, and of the 1st and 2nd Light Dragoons of the King’s German Legion. In the rear of this brigade stood the Cumberland Hanoverian Hussars, under Lieutenant-Colonel Hake. In the right rear of Altern’s Division, further to the left, stood the 3rd Hussars of the King’s German Legion, under Colonel Sir Fredrick Arentschildt. On the right of the Charleroi road, and in the rear of Alten’s division, Major-General Lord Edward Somerset’s 1st or Household Brigade was drawn up – the 1st and 2nd Life Guards (Blue), and the King’s Dragoon Guards. On the left of the Charleroi road, in rear of Picton’s Division, stood the Second or Union Brigade – 1st Dragoons (Royals), 2nd Dragoons (Scots Greys), and 6th Dragoons (Inniskillings), under Major-General Sir William Ponsonby. Again to the left, the Fourth Brigade was posted – 11th, 12th and 16th Light Dragoons, under Major-General Sir John Vandeleur; upon the extreme left of the whole army was the Sixth Brigade, consisting of the Tenth and 18th Hussars and 1st Hussars of the German Legion, under Sir Hussey Vivian. The reserves consisted of the Dutch, Belgian, the Brunswick and Hanoverian cavalry, and were posted in rear of the centre within the roads from Charleroi and Nivelles.

On the morning of the 18th a reconnoitring party was sent out from the Sixth Cavalry Brigade, by order of Sir Hussey Vivian, to guard the left flank of the British Army, which was much exposed, and also in hopes of gaining some intelligence in the near approach of the Prussians. This patrol was taken from the Tenth Hussars, and was under the command of Major Taylor, who proceeded with it in the direction of Ohain, and placed his piquets at Ter La Haye and Frischermont. About ten in the morning a Prussian patrol was met with, when the officer in charge of it informed Major Taylor that General Bülow was at St Lambert, advancing with his corps d’armee. Major Taylor immediately dispatched this important intelligence by Lieutenant Lindsey to the Duke’s Headquarters, besides reporting it to Sir Hussey Vivian.

About eleven o’clock the massive divisions of the enemy were seen advancing.[8] The infantry in two lines covered by skirmishers and flanked by regiments of lancers, moved forward to the music of their regimental bands. Thus formed, it presented a magnificent and imposing site. Cuirassiers followed in the rear of the centre of each infantry wing, lancers and chasseurs marched behind the cuirassiers on the right wing, and the Imperial Guard, supported by the Sixth Corps of Cavalry. No less than 246 pieces of ordinance were distributed along the front and on the flanks of the first line, and these were kept in readiness to open fire on the British position.

At 11.30 A.M. Prince Jerome’s division attacked Hougoumont, on the English right. Attack quickly succeeded to attack, each made with the impetuosity characteristic of the onset of French troops, but all without avail, and their finest efforts proved ineffectual. The British left was next attacked by the French at about 12.30 P. M. “Upon the extreme left of the first or main line,” says Siborne, was stationed Vivian’s Light Cavalry Brigade, comprising 10th and 18th Hussars, and the 1st Hussars of the King’s German Legion. The two former regiments were in line in the rear of the Wavre road, and within a little from the crest of the ridge; the right of the 10th resting upon a lane leading from Smohain in the direction of Verd-Cocou. The 1st Hussars, King’s German Legion, were also in line and formed in reserve. The left of the brigade was completely en l’air upon high, open and flat ground … On the right of Vivian’s Brigade, and having its own right resting upon a narrow lane, forming a light hollow way lined with hedges, stood Vandeleur’s brigade of light cavalry, consisting of the 11th, 12th and 16th British Light Dragoons, in columns of squadrons. The lane on which its right rested, descending interior slope of the position, joined the other lane which lead from Vivian’s right to Verd-Cocou. This advance of the French troops was confronted by Vandeleur’s Dragoons and the 10th Hussars, whilst remaining regiments formed the reserve.[9]

The Earl of Uxbridge, seeing that a favourable opportunity presented itself for the use of his cavalry, gave orders for a simultaneous charge of the two heavy cavalry brigades under Lord Edward Somerset and Sir William Ponsonby, the former against the enemy’s cavalry, the latter against the masses of French infantry. Somerset charged the enemy’s cuirassiers, who were suddenly thrown out of their speed by coming on a hollow way. Being taken in flank as well as in front, they were broken up, driven back and pursued by the 2nd Life Guards. No sooner did Ponsonby perceive the Household Brigade with the King’s Dragoon Guards in motion, than he led on his own brigade, the Royals and Inniskillings in the first line, the Greys in support. With these he attacked the French infantry divisions advancing under General Allix. The Greys, coming up on the left of the front line, charged with it, and our Dragoons, having the advantage of the descent of the hill, bore down the mass of men in front of them. The whole were in a moment jammed together, when gradually a scattering flight from the rear loosened the unmanageable mass, which now rolled back. The charge of the Union Brigade having thus succeeded, the three regiments then rallied and fell back before the large bodies of French cavalry brought to bear upon them.

Vandeleur’s brigade now moved up in support, as Ponsonby’s brigade was suffering severely from the lancers and chasseurs under Jaquinot. It was just at the right moment that the 12th and 16th Dragoons, in columns of divisions, rapidly moved over the crest of the hill. When half way down, forming line to the right, they dashed through a column of French infantry so as to reach the right flank of French lancers, whom they drove down the hill in complete disorder and confusion.

Perceiving Ponsonby’s brigade in disorder, Vivian had ridden forward from the extreme left and descended some distance down the slope to gain a better view for his own personal guidance. With practical judgement he soon came to a conclusion what the result of this affair might be, and immediately dispatched orders to the 10th and 18th Hussars to move up along the hollow to the right leaving, however, the 1st Hussars, K. G. L., to protect the flank. But as the charge of Vandeleur’s brigade had succeeded without the active aid of his own support, the 11th Light Dragoons, the further advance of the 10th and 18th Hussars was stayed. They continued, however, in their new position on the right of the lane leading to Verd-Cocou.

It was now about half-past three o’clock, and Napoleon, finding that his infantry had been able to make little or no impression upon the British position, determined to try the effect of repeated charges by his splendid cavalry under Marshal Ney upon the British centre and left.

By this time Vivian’s brigade had been drawn still further from the left to strengthen the centre of the line. It had scarcely taken up its new position when Colonel Quentin, at the head of the Tenth, was wounded in the ankle, and the command of the Regiment devolved to Lieutenant-colonel Lord Robert Manners. Immediately after this occurrence the enemy made another desperate attack upon the British centre, which had so far succeeded as to dislodge and drive back some battalions of Brunswick infantry. Just then the Sixth Brigade, with the 10th and 18th Hussars in front, and 1st Hussars K. G. L. In reserve, drew up in rear of these troops (Brunswick Infantry) relieving the exhausted remnants of the Scots Greys and Third Hussars, King’s German Legion. The presence and appearance of this fresh cavalry tended very considerably to restore confidence to that part of the line. The allied infantry were, however, on the point of once more giving way. The Nassauers were falling back en masse right against the horses’ heads of the 10th Hussars, but these, by keeping their files closed, prevented further retreat. Vivian and Captain Shakespeare, of the Tenth (who was acting as his Aide-de-camp) rendered themselves conspicuous at this moment by their endeavours to halt and encourage the Nassauers.[10]

The Hanoverians, with the German Legion on the left, led by Kielmansegge, now resolutely dashed forward at the double, their drums beating. The Brunswickers took up the movement, as did also the Nassauers; Vivian and his aide-de-camp cheering them on, whilst the Tenth Hussars followed in close support. His brigade, by its close proximity to these troops, against which so close and unremitting a fire of musketry was maintained, was placed in a very trying position for cavalry, and suffered much in consequence. It was here that Captains Grey, Gurwood and Wood of the Tenth were wounded.

CHAPTER XIX

The Prussians under Blucher arrive – Vivian’s Brigade ordered to advance – The Tenth charge the Imperial Guard – Death of Major Howard – Lines by an Officer of the Tenth – Byron’s “Childe Harold” – List of Officers Present – List of Killed and Wounded

During all this terrible conflict the Prussians from Wavre were struggling steadfastly on to Wellington’s assistance. Muddy, bad roads all but stopped their progress, and had it not been for the determination of “Old Marshal Forward,” as his soldiers named Blücher, their commander, he and his army would not have reached the field of Waterloo that night. When the Prussians were seen and their guns heard on the British left, Napoleon made a final effort to break Wellington’s line by bringing up his Old Guard, which as yet had taken no part in the battle. This was certainly the most critical part of the action.

It is well known how Napoleon’s last charge failed, and how, with more fresh battalions, he stove eagerly to incite the Imperial Guard to new efforts. Then it was that the Duke at last found himself enabled to become the assailant. Knowing that his left was now protected by the Prussians, and that he had the Hussars Brigade under Vivian fresh and ready at hand, he, without a moment’s hesitation, launched them against the cavalry near La Belle Alliance. The best description of the part taken by the Tenth in this memorable charge is found in the following passages from Siborne:-

“Vivian, the moment he received the order to advance, wheeled his brigade half squadrons to the right. Thus the Tenth Hussars became the leading Regiment, the 18th Hussars followed, the First Germans moved off in rear of all. As the column passed by the left front of Vandeleur’s brigade it was saluted by the latter with cheers of encouragement, and in a similar matter by Maitland’s Brigade of Guards as it passed their flank. On arriving about midway, Vivian observed French bodies on the left of La Belle Alliance, posted as if fully prepared to resist the threatened attack, and he at once decided upon attacking them. Continuing the advance in the same order, he, with the view of turning the left of the enemy’s cavalry, ordered the Tenth Hussars too incline to the right, a command which was followed by ‘Line to the front on the leading troop in succession by regiments,’ the two corps behind being ordered to follow in support of the Tenth. The rapid pace which had been maintained by the head of the column, combined with the incline to the right which had been made, rendered it difficult for the rear troops to get up into line, and as Vivian sounded the ‘charge’ as soon as the first squadron was formed, it was executed not in line, but by echelon of squadrons, which under the circumstances, was the preferable and most desirable formation, for before the left squadron of the Tenth had dashed in amongst the enemy’s cavalry, the latter were in full flight. Seeing the success of the charge, Vivian at once ordered the ‘halt’ and ‘rally’ for the Tenth, while he directed the 18th Hussars to attack the Chasseurs and grenadiers a cheval. When the charge of the 18th began, some French artillery attempted to cross the front at a gallop, but the attempt failed, and after capturing the guns, the 18th bore down upon the cavalry, who were soon driven from their position and flying along the high road. Just as the ‘halt’ and ‘rally’ was sounded for the Tenth, the right squadron, under Major the Hon. F Howard, was attacked on the flank by a body of cuirassiers and forced about a hundred yards away to the left, while the other two squadrons, nor being aware of Vivian’s order to ‘halt’, continued the pursuit under Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Manners.

“Sir H. Vivian having seen the 18th charge, and being satisfied with its success, was hurrying to bring up the remaining regiments of his brigade, the 1st German Hussars, when he met with Major Howard’s squadron, close to the square of the French Grenadiers of the Guard. General Vivian doubted for a moment how far it might be advisable to attack the square, but seeing one of our infantry regiments advancing, and calculating on its immediately charging the face and angle of the square next to it, ordered Major Howard to charge the face and angle to which he was opposed. This was executed with the greatest gallantry and determination, Vivian himself joining in the charge on the right of the squadron. The hussars charged home to the French bayonets, when a fierce conflict ensued, Major Howard being killed at the head of his men. He was shot in the mouth and fell senseless to the ground, when one of the Imperial Guards stepped out of the ranks and beat his head with the butt of his musket. Two other officers – Lieutenants Arnold and Bacon – were wounded, and Cornet Hamilton, who rode as a serrefile, brought the squadron out of action. Lieutenant Gunning was killed immediately previous to the attack. In consequence of the infantry regiment not joining in the attack, the square, a very strong one, cannot be said to have been broken by the shock, for the veteran soldiers of whom it was comprised knew all too well of their power of resistance against such a handful of horsemen; Still, the square fell slowly back until it reached the hollow formed by the narrow road that led from the causeway in rear of La Belle Alliance towards the left of the French position, into which, descending in confusion, the Guards went to swell the hosts of fugitives, hurrying along the general line of retreat of the French army.”

Meanwhile, the remainder of the Tenth Hussars, consisting of the left and centre squadrons, had, under Lord Robert Manners, continued its course down into the valley south-east of the Hougoumont enclosures, and drove back the French Cuirassiers. They now came upon the retreating infantry, many of them wearing the large bearskin caps, showing them to be the Imperial Guard. They seemed seized with a panic as their routed cavalry dashed past them, and they commenced throwing down their arms, numbers of them loudly calling “Pardon”.[11] Then crossing the same narrow road before mentioned, the Tenth brought up their right shoulders ascended the height in rear of the hollow way. Upon the slope of the hill about half a battalion of French Guards had rallied and formed, with some cavalry close behind them, and opened a sharp fire upon the Tenth. Lord Robert Manners halted for a minute when within about forty paces from them, to allow his men to form up. He then gave a cheer and charged, when the Imperial Guard and cavalry instantly turned and fled. The very forward movement of Vivian’s brigade, and the vigorous attack which it made against the centre of the French position, having rendered an immediate support imperative, Vandeleur’s brigade was despatched across the ridge in column of half squadrons, right in front, at the moment of general advance in line.

So, as Siborne goes on to tell us, “Vivian’s brigade, which had not only broken but completely pierced the centre of the French position, had its right effectually protected by Vandeleur’s advance, while its left was secured by the advance of Adam’s brigade of infantry, which, operating along the left side of the Charleroi road, was pushing the enemy’s routed forces further and further from the field of battle.[12]

The following extracts are taken from some line written by an Officer of the Tenth Hussars who was present at the repulse of the last attack made by the French:

‘Tis Vivian, pride of old Coimbra’s halls,

His veins th’untainted blood of Britons fills,

Him follows close a Manners, glorious name

In him a Granby’s soul aspires to fame,

Or such as erst, when Rodney gained the day,

Ebbed from his kinsman’s’ wound with life away.Then pierced the fatal ball young Gunning’s heart;

Headlong he fell, nor felt one instant’s smart;

Calm, pale as marble form on tombs, he lay

As days had sped since passed his soul away,

His charger onward, on the squadron’s flank

To battle rushed, keeping its master’s rank.Charge! Howard charge! And sweep them from the field;

To British swords must their bayonets yield,

To high emprise, upon the battle’s plain,

When was the name of Howard call’d in vain?

Worthy his great progenitors, he heard

Vivian’s call exulting, then, with ready word,

“Tenth Hussars charge!” he cried, and wav’d on high

His gleaming sword: forward at once they fly.

Thus rushed the gallant squadron on the foe,

Yet firm they stood, their arms in levell’d row,

Their volleying thunders poured our ranks among,

Where foremost blade on foremost musket rung,

Three gallant youths, the van, exulting led,

Three by the deadly volley instant bled.Arnold and Bacon fall, again to rise

From three fell wounds brave Howard’s spirit flies,

Full many a warrior on that dreadful day,

Brave, generous, gentle, breathed his soul away,

But one more gentle, generous or brave,

Never in battle found a soldier’s grave.

As the moon rose and gradually shed its light over the field, the retreating line of the vanquished foe became by degrees perceptible. Wellington, who had led the advance of Adam’s infantry and had seen how crushing and complete was the defeat, returned to his main body. When he reached La Belle Alliance, he gave the command for the whole army to bivouac upon the field of battle. Adam’s brigade passed the night upon the spot it had reached; Vandeleur’s on the right near the woods of Cellois; While Vivian, inkling somewhat to his right, led his Hussars much further in advance of the army, establishing his bivouac close to the hamlet of Hilaincourt.

The following is a list of Officers of the Tenth Hussars who were present at the actions of the 16th, 17th and 18th of June:-

| Lieutenant-Colonels | George Quentin (severely wounded) |

| Lord Robert Manners (Brevet Colonel) | |

| Major | Hon. F. Howard (Killed) |

| Captains | T. W. Taylor (Brevet Major) H. C. Stapleton, |

| J. Grey (wounded), J. Gurwood (wounded) | |

| C. Wood (severely wounded), H. Floyd | |

| A. Shakespeare (Acting A. D. C. to Sir H. Vivian) | |

| Lieutenants | J. W. Parsons, C. Gunning (Killed) |

| W. S. Smith, H. J. Burn, | |

| R. Arnold (wounded), W. Cartwright, | |

| J. C. Wallington, E. Hodgeson | |

| W. C. Hamilton, A. Bacon (severely wounded) | |

| W. H. B. Lindsey, | |

| Paymaster | J. Fulton |

| Lieutenant & Adjutant | J. Hardman |

| Assistant Surgeon | J. Hardman |

| Veterinary Surgeon | H. C. Sannerman. |

The casualties in the Tenth were: Killed, two Officers and 21 rank and file, and fifty-one horses.

List of Killed: Major the Hon. F. Howard, Lieutenant C. Gunning, Privates John Falea, Richard Freemantle, Robert Kent, George Hemming, Evan Price, Edward Rosewell, Thomas Gadson, John Taylor, Charles Porter, John Taites, Joseph Wyatt, Samuel Deacon, John Dowling, James Ashwin, Robert Swingler, Henry Gander, Samuel Jenkins, William Wanstill, Samuel Lee, W. Green, Joseph Derry.

The wounded were six Officers, one troop quarter-master, one trumpeter, thirty-eight rank and file and thirty-five horses. Missing, one trumpeter, twenty-five rank and file and forty-one horses.

On the morning after the battle a party under Lieutenant W. Slayter-Smith, consisting of Sergeant Plowman and six men, were sent back to the field of action to bury the dead of the Regiment and to bring away any who were wounded. In the execution of this duty the party found the body of Major Howard, which they interred between two trees near the spot where he fell.

Lord Byron, in a note to “Childe Harold” thus described the place: “My guide from Mount St Jean, over the field seemed intelligent and accurate. Where Major Howard fell was not far from two tall solitary trees (there was a third cut down or shivered in the battle) which stand a few yards from each other at a pathway’s side. Beneath these he died and was buried. The body has since been removed to England. A small hollow for the present marks where it lay, but will probably now be effaced; the plough has been upon it and the grain is now ripening. After pointing out the different spots where Picton and other gallant men had perished, the guide said “Here Major Howard lay, I was near him when he received his death wound.” I told him my relationship and he seemed then still more anxious to point out the particular spot and circumstances. The place is one of the most marked in the field, from the peculiarity of the two trees above mentioned.” Lord Byron has immortalised the death of his kinsman in the following lines:-

Their praise is hymned by loftier harps than mine,

Yet one would select from that proud throng,

Party because they blend me with his line,

And party that I did sire some wrong,

And partly that bright names will hallow song,

And his was of the bravest, and when showered

The death-bolts deadliest the thinn’d files along

Even where the thickest of war’s tempest lowered,

They reached no nobler breast than thine, young gallant HowardThere have been tears and breaking hearts for thee

And mine were nothing, had I such to give,

But when I stood beneath the fresh green tree

Which, living, waves where thou didst cease to live,

And saw around me the wild field revive

With fruit and fertile promise, and the spring

Come forth, her work of gladness to contrive

With all her reckless birds upon the wing,

I turned from all she brought to those she could not bring.

APPENDIX

The following letters are appended, and from having been written on the spot, will prove of considerable interest.

A SHORT ACCOUNT OF THE BATTLE OF WATERLOO

Letter from General William Cartwright, then Lieutenant in the Tenth Royal Hussars, aged eighteen

Waterloo, near Brussels

19th June, (Monday after Waterloo)

MY DEAR FATHER, Although I have seen many battles in my life, I assure you they were a complete farce to one for this last three days. Bony, against us, fought like a tiger; we fought like Englishmen, and thanks to God, repelled him with great loss. Our Cavalry behaved so finely that everyone, when they saw us, were quite thunderstruck. Poor Gunning was killed, as also Bouverie. I only wonder we were not all killed. I have lost all my baggage, and therefore intend taking Gunning’s, and you will pay Mr Gunning, I have no doubt. Thank God I have been luck enough to escape. I commanded a troop on this occasion. We charged four or five times our numbers – the men in armour – but we made a pretty hole in them; there are not above six officers left with the Regiment, I command a squadron now. We have been fighting since the 16th. I will give you another account in a day or two, but in the meantime excuse this scrawl. We are within three leagues of Brussels.

In haste, &c., &c.,

Your most affectionate Son

Wm. CARTWRIGHT.

{SECOND LETTER.]

Three days after Waterloo – on the advance

MY DEAR MOTHER, – Having at length a day’s halt, I take the opportunity of writing to you, to give you some account of our proceedings, which commenced on the 16th, which day about 4 o’clock A. M. we were routed out and marched to Nivelle. It was just about 7 P. M. when we reached that place, but as the scene of action was about two leagues on, we trotted in and got to the field of action just before dusk. We bivouacked there the whole night, and the next morning the skirmishing again commenced. This lasted until about 10 o’clock, from 4 in the morning, when the Duke, our noble commander, having heard that Blücher (who was on our left) had been repulsed, he determined to retreat in order to communicate with this old gentleman. Accordingly, the infantry all went to the rear, and the Hussars – for they are always more employed than any other cavalry – were to cover the retreat. The Hussars’ general, Sir Hussey Vivian, appointed our regiment and the 7th to this unpleasant duty, for such it is. We showed front to the enemy for two or three hours after the army had retreated, till at last the enemy brought up a very large force of Cuirassiers, who were all in armour. We were then forced to retreat, and of course these fellows followed us up. We fought and retired, and so on, till at length we came up our infantry, who were in position. We then took our post, and a great deal of cannonading &c., ensued. We bivouacked on top of the position this night (27th), and a pretty rainy one it was. I was never so wet and miserable in my life. The next morning of course, we expected an attack, but nine o’clock passed, and nothing new, so nothing until 11, when our piquet was driven in. Of course we all turned out immediately and took our place in our position, which I assure you were rather formidable. The enemy then brought on very heavy columns, both of infantry and cavalry. All of our awaited the attack, which was conducted by Napoleon himself, and with great vigour; they made attacks every moment, bringing on fresh troops every time; but our fellows, fighting more like lions than men, managed to keep them down. He had about 130,000 in the field; we had not more than 70,000, including everything, Hanoverians &c. Of course, numbers will tell at last, and our right began to waver – this was on the main road. We then moved from the left, which was our former place in the position, to the right, and supported the infantry in some style. We were kept under the heaviest fire which was ever heard, both of musketry and cannon, for some time. (About 7 P. M.) However the Prussians at length made their appearance on the left, and began with the enemy. This gave us double spirit and we went on like tigers – we actually went up to the mouth of the cannon. Whilst we were thus engaged, the enemy heard the Prussians on the left; this they did not seem to like, and we of course pushed on some more. However, our Commandant of the Brigade, Sir Hussey Vivian, ordered us to form in column right in front; this brought me, as I was commanding the right troop, in front. We then went on and the enemy formed in squares – we did not mind this, but deployed as steady as if we were at a field day. It was just here that poor Gunning was killed. We then moved on and came to the charge. The squares of course made a desperate resistance, but our valour soon extinguished their squares. Their cavalry came down with Lancers, armour &c. enough to frighten us, but we charged them, though twice our number, and quite panic struck them; some ran off, others were tumbling off their horses; others attempted to defend themselves, and so on. We however gave a pretty fair account of them. After this they brought on more cavalry, but we played them the same trick. We took an immense number of prisoners, cannon &c. &c., and flatter ourselves we were the means of saving the day. I will give you a copy of the orders issued by our commander, as follows:

“Major General Sir Hussey Vivian begs to express in the strongest possible terms to the brigade he has the honour and pleasure to command, the infinite admiration with which he beheld the conduct of the regiments composing it in the memorable and glorious battle of yesterday. The attacks of the 10th and 18th Hussars were made with that spirit that ensured success, and the second attack of the Tenth Hussars, on a square of infantry, was a proof of what discipline and valour can accomplish. The Major-General desires that every individual Officer, and those engaged on the plains of Waterloo, will, together with the strongest expression of his approbation, accept his very best thanks for their valour and steadiness. (Sd) Hussey Vivian, Major-General.” What can be more satisfactory than the above order? Besides this, there is a letter despatched to the Prince about the Regiment. We have just been giving them a taste of the new Tenth. Having lost everything I had, horses included, I have just got poor Gunning’s baggage up. I must take it, and intend getting it valued by our adjutant, which is the regular manner, and then send the account to my father. We intend to be in Paris in a fortnight. Nobody knows where Boney is. They say we are to have another battle at Laon, where he is making a stand. The rascals killed all the prisoners they took. We are not working on their principle. The Prussians are following them up on our left. You will see by the “Gazette” that the cavalry had a very far share in the battle. I must now conclude, as I am going to put on a clean shirt for the first time since we began.

Adieu, my dear mother. Pray excuse this scrawl, and forgive all faults, and believe me &c. &c.,

Wm Cartwright.

The following are extracts from letters of Captain Charles Wood, 10th Hussars, after he was wounded in battle:-

I got hit just as the Duke moved to the attack and bled like a pig. I took up my stirrups in the hunting seat and made the best of my way back to Waterloo. With the assistance of a dragoon, I afterwards got into Brussels, and found a lodging in the Rue Royale. Arnold[13] will come home with me. He was shot through the lungs. They tell me he must not eat meat for six months. He says “Wait till I get to Northampton with five hunters next November…” Quentin is going to Paris tomorrow in a carriage … Bob Manners was struck in the shoulder by a lance, and did not find it out until the next day. … You should have seen us the night before the fight. Every one wet through. We had a shower that came down like a wall. Our horses could not face it and all went about. It made the ground up to the horses’ fetlocks. We got into a small cottage close to our bivouac, about a mile in rear of our positions, most of us naked and getting out things dry at the fire. I managed to get “Paddy”[14] a shop for the night. Old Quentin burnt his boots, and could not get them on … We had to feed on what we found in the hut, beginning with the old hens for supper, and young chickens for breakfast. I see the English papers say “The Light Dragoons could make no impression on the French Cuirassiers.” Now our regiment actually rode over them. Give me the boys that will go at a swinging gallop for the last seventy yards, applying both spurs when you come within the last six yards. Then if you don’t go right over them I am much mistaken. …. I have found the ball which went through my thigh into the pad of my saddle, very high up. I think it hit the bone which drove it upwards.

Letter from Lieutenant Lindsay to his mother, Lady G. Lindsay, written from the field of Waterloo; it was sealed with a wafer made of pinched bread.

MY DEAREST MOTHER, We have just had the happiness of giving the French the most complete drubbing they ever got, having beaten them on the heights of Waterloo, destroyed nearly their whole army, taking nearly a hundred pieces of cannon. They drove in a piquet of the Tenth on which I happened to be, at ten o’clock, and a charge of the Tenth on the 18th decided the fate of the day. Nearly the whole of their officers had either been killed or wounded, and, thank God, I escaped without the least accident. I write this in the most shocking place you ever saw, but you must be satisfied with it until I can write a fuller account. We are about to pursue them immediately. The Prussians have saved us that trouble, for they have followed them. Eight officers are the whole we can muster. Most are killed or wounded. Adieu my dearest mother, with thousand loves to all.

W. F. B. LINDSAY

.

[1] See Siborne p. 163

[2] Siborne

[3] See Siborne p. 168

[4] Ibid

[5] Ibid

[6] Alison

[7] Ibid

[8] Napoleon delayed his attack until so late owing to the deep state of the ground after the rain, which was much against his strongest arm, the artillery.

[9] Siborne

[10] Siborne

[11] Siborne

[12] Napoleon and his aide-de-camp, Gourgaud, both ascribed the loss of the battle to this happy charge of Vivian’s brigade on the flank of the Old Guard. “Le soleil” says Gourgaud, “était couche; rien n’était désespère, lorsque deux brigades de cavalerie ennemie, qui n’avaient pas encore donne, pénétrèrent entre La Haie Sainte et la corp du général Reille. Elles auraient pu être arrêtées par les huit carres de la Guard, mais, voyant le grand désordre qui régnait à la droite, elles les tournèrent. Ces trios milles chevreaux empêchèrent tout ralliement.” – Alison. To the same purpose Naploeon says in his despatch “Sur les huit heures et demi, les quatre bataillons qui avaient été envoyés pour soutenir les cuirassiers marchèrent à la baïonnette pour enlever les batteries. Le jour finissait, une charge faite sur leur flanc par plusieurs escadrons Anglais les mirent en désordre.” – Napoléon Bulletin sur la Bataille de Mont Saint-Jean 21 Juin 1815. Marshal Ney also states: There still remained for us four squares of the Old Guard, advantageously placed to protect the retreat. These brave grenadiers, the choice of the army, forced successfully to retire, only yielded ground foot by foot, till, finally overwhelmed by numbers, they were almost entirely annihilated.”

[13] Wounded in the charge on the French square

[14] His charger

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.