The following piece was published in the Xth Royal Hussars Gazette in April 1911, a magazine of which my Grandfather, Major Roland Pillinger, was editor from its inception in 1906. I have copied it exactly as it appeared in issue 15, Volume IV.

The Battle of Waterloo

Before another XRH Gazette appears the ninety-sixth anniversary of the great battle of Waterloo will have passed.

It was fought on the 18th June 1815, and we, as all soldiers of Regiments who took part in the conflict must inevitably do, on the 18th June 1911 will reflect with pride that the Tenth not only participated in the glorious day, but also that the share of the Regiment in the battle helped decisively to attain the glories to Great Britain which resulted.

The least informed students of the history of our country are acquainted with the far-reaching influence of the overthrow of the great soldier Napoleon, by Wellington, not only on our Empire, but on every nation in Europe, and the story of Waterloo is one that never palls, one of which repletion can never bore us. Therefore, with these convictions we give a verbatim copy of a letter,(From the original.) written just one month after the fateful day by a Tenth Hussar, who assisted to add for Britons, for all time, one of the brightest pages in the world’s history .

In no way can we be brought so closely face to face with the incidents of the fight as by the account given by an eye witness; in no manner can we see so vividly the wavering fortunes of the varying phases of the Titanic struggle as by the narratives of actual participators, whose simplicity of language and terms impart most eloquently, and transmit most clearly, the occurrences they describe.

The writer, Captain Thomas W. Taylor’s allusion to service in India is explained by the fact that he served for seven years in that country as A. D. C. to the then Governor General (Lord Minto), returning to England in 1814. Hence also, his jealous regard for the reputation of his arm, which he suspected might be depreciated in the circles of Calcutta.

As set forth in his letter, he was on piquet on the morning of the day of Waterloo, and history adds, that he personally conveyed to the Duke of Wellington the important despatch reporting the advance of Blucher, which was delivered to him by a Prussian Officer of the staff.

By the death of Major Howard in action, Captain Taylor obtained the Regimental majority and a brevet Lieutenant-Colonelcy. He went on half-pay in 1825, but the following year was appointed commandant of the Cavalry Riding Establishment at St. John’s Wood, which appointment he held until 1831. In 1833 he became Groom of the Bedchamber to His Majesty King William IV., and in 1837 was appointed Lieutenant-Governor of the Royal Military College, Sandhurst. As A. D. C. to General Gillespie he took part in the expedition to Java, and received the silver medal with clasp, the Waterloo medal, and Companion of the Bath. He died on the 8th January 1854.

On piquet, Champs Elysees

July 16th 1815

My Dear Brownrigg

When I left India, if anyone had told me, that in little more than a year I should be doing duty in the Champs Elysees, with the Tenth Hussars forming part of a victorious army in possession of the capital of France, could I ever have brought my mind to believe it? Perhaps I could if anyone could, because, you know, I was always sanguine in my hopes; but it would have been difficult.

Yet so it is, and what is curious enough, within 5 months our Regiment has been employed, as well as many others, in keeping in order both London and Paris, for we had just quitted London and the Corn Bill Mobs when we received orders to embark for Ostend.

Mrs Taylor, Harriet and the children were in Dorsetshire at the time, so I set off to fetch the two former, and after spending a week at the White Hart in Rumford, they accompanied me on the march to Gravesend, Sittingbourne, Canterbury, and Ramsgate; there I took leave of them on the 16th April and sailed with three Squadrons of our Regiment for Ostend. From thence we marched to Bruges, Ghent, and Audenarde, to Voorde near Ninove, about 20 miles from Brussels; there we remained in quarters, pleasantly enough, from the 2nd May to the 16th June. In my march, near Ghent I met Fielding, travelling post from Italy, with some despatches. During our stay at Voorde I was often at Brussels, and paid a visit to Antwerp. On the 15th June I was at Brussels and returned late that evening. We were ordered to a field-day next morning, but on the 16th, at 4, received an order for full marching order immediately. We marched about 6, to Enghien, about 14 miles – no halt – about 4, halted in close columns of Brigades: (ours is 10th, 18th, and 1st Germans, and one troop Horse Artillery, under Sir H. Vivian.) and fed, mounted again, passed through Braine-le-Comte; on coming out of a thick wood beyond heard firing; at last saw a long line of smoke, firing very heavy – got our orders to “trot and throw away forage” — trotted at a rate of 8 miles an hour (the ordered pace) through Nivelle, the ordered to proceed along the Namur Road, went about 5 miles same pace along the Chaussee, or paved road, nearing the firing and meeting wounded; At last, at about 9, near dusk, form half squadrons, and gallop up in column, on the left of our position, just time enough to have a shell or two fly over us; one killed a horse of the 18th, but the Battle of Quatre Bras (the place we had got to) was over, except skirmishing with the retiring French, and now and then a cannon shot. It had been a tough job, our Infantry had, as usual, done all that could be done, and had acquired an advanced position after hard fighting. The Guards had suffered a good deal in a wood that had been the scene of contest, and was full of dead and wounded. The French Cuirassiers had made some gallant attacks, had broken the 69th and taken their colours, but had been tickled in turn and lay in heaps, at one place. The Duke of Brunswick’s A. D. C. was killed – a great loss as he was a fine fellow. The Prussians had been sharply engaged at Ligny all day, and we thought at night had been victorious. We retired about half a mile at 10, dismounted, and lay down in a wheat field, pleasant for man and horse after a march of above 40 miles, – the last eight at a good pace.

At 2.30 a.m. on the 17th, popping began again and there was sharp firing until about 10 o’clock along the advanced post; we were dismounted on a hill, and saw it all. I expected a general action. We then heard the Prussians had got a good thrashing the day before, and had fallen back, leaving our left uncovered; accordingly we must budge too, so the heavy guns and infantry began to retire. We were ordered to advance and form in echelon of Squadrons. The French were all cooking, apparently by their fires. About 12 we discovered large bodies of cavalry coming over a hill (they say they had 16,000) and forming close column.

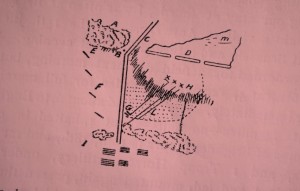

|

- Wood contested on 16th

- Large house, Quatre Bras

- Nivelles & Namur Road

- Hussars in line on hill

- Squadron of Light Dragoons

- 10th In echelon of Squadrons

- Picquet of Squadron of 18th

- Horse Artillery guns firing at cavalry of French debouching

- Close columns of French cavalry prepared to advance

- French Infantry lines

I describe this, not on account of anything important, but to give you an idea of the prettiest specimen of the ballet of war that could be. The duke came down to our Regiment with Lord Uxbridge, looked at the French cavalry, gave a yawn, and said “Well, I suppose we must retreat.” So we retired and found the whole Brigade on the hill. The Tenth began skirmishing at G, retiring: out came the French Cavalry Lancers (they looked very gay, white and red facings, and red a white flags on their lances.), formed a squadron, skirmishers in front, skirmishing with 18th retiring. We saw all this like a play, from the hill: more Squadrons of French forming in the wheat field; our guns fired some rounds at the road, knock some over but they are not checked; guns limber up and retire, we retire in line.

The Heavy Cavalry and Light Dragoons lines in rear of us retire also. As we got down into a dip the French began to throw shells – one burst near the 18th and killed a man – they were prettily thrown. Just then thunder, lightning and rain that would do credit to a Nor’Wester – there was something of the sublime in the scene: we filed off into narrow roads, beyond; the 1st Germans leading us in the centre, the 18th in rear skirmishing; the other Cavalry retired along the Great Road, which, I am happy to say, the French preferred (our roads were very bad from the rain) so we heard them pounding away on our left, and every now and then the Hurrah of a charge. The French cavalry came on in fine style, the Lancers in front, all half drunk. The Life Guards and Blues charged them, bent them and drove them back some way, but they were pressed on by large columns in rear, and supported by artillery. The 7th were charged in front and flank by them, in a village, and lost nearly one division, and Major Hodge and the Adjutant killed. They piked Hodge after he offered to surrender. Ld. Uxbridge exposed himself much; a Captain Krancherely of the 3rd Hussars was taken, but escaped afterwards, and Smith of ours, who had joined that column by accident, and generously lent his horse to Gordon of the 7th, who was wounded, and had lost his own, to take him to the rear, was on foot amongst them, with purse and sword, ready to give up; but in the row they took no notice of him and he got off.

We had a long march in bad roads and hard rain, at last marched into a coppice, formed close column, and bivouacked for the night; here was a specimen of the comforts of war; wet thro’ in a wet coppice, hard rain, and a victorious French army (i. e. over the Prussians) in front a menacing to give us a good drubbing and plunder Brussels. We lit fires and lay down by them, and at last got into a cottage, when bread and beer with a pipe set all right, and we strewed the floor. Next morning, 18th, soon after daylight, my Squadron, (the centre) was ordered for piquet, to relieve the 18th.

I went about a mile and a half in front, – to a village, Ohain in a deep valley, and posted my piquet there, and my advanced posts and Vedettes on a height beyond; the post of the Vedettes saw some French cavalry on the move on the other side of the alley. When I thought I hade made all secure (in the village we had Hanoverian Infantry), set some fowls and bacon boiling – when a Officer of Prussian Cavalry arrived with a Patrol, and desired me to inform the Duke of Wellington instantly that General Bulow was arrived at St Lambert, three quarters of a league off, with his corps d’armee, which I did accordingly – this was good news. Bulow had been sent to keep Saxons in order, and his absence was much felt by the Prussians on the 16th; soon after one of my Vedettes came to inform me the French were advancing. I went to the front, saw three or four Squadrons advancing towards us – the village being occupied by Infantry, and a defile in itself, withdrew my Squadron and formed in the open in rear to protect the retreat of the Infantry if necessary; set off an Officer to report the advance of the French, out line was under arms in a short time; there was a good deal of firing about Ohain, and a farmhouse near it, the Hanoverians keeping possession well, the French Cavalry parading about the other side, but I was soon convinced the fight would not be there. Our guns were brought up, and the rest of the Regiment to support them, but did not fire. The French brought up guns and began to cannonade the Foreign Infantry on our right and guns, which answered them; the there was cannonading all the way down the line, and a heavy firing on the right, (that is, to the right of us, but near the centre of our line, I believe) as of a general attack.

Our Brigade moved to right and formed line, still on the left of the position. We got then into cannonade, and from that time, about 12, never could be said to be out of it until the end of the battle, about 9 at night; for a long time we were formed on the ridge of the hill, exactly in the range of the enemy’s guns, which threw shot and shells without intermission, but it is wonderful how little effect as I heard a man – a Sergeant of the Horse Artillery, which were close before us in a line, say – “I suppose they are firing at that close column, and our guns, and a pretty range they are making of it.” However, the range was not always so bad. I believe it is allowed on all hands, that a heavier cannonade had ever been known. The French had at least 150 pieces against us, and we had upwards of 100. Buony, in his first despatch, and very true and just it was, except as to numbers, said “he supported his grand attack on the right centre with 80 pieces of cannon.” At this time the Heavy Cavalry made some fine charges, and the Light Dragoons charged at different times: they said Lord Uxbridge was displeased with some Regiments. We were not ordered to attack, and I began to think, kept in reserve to cover a retreat. We knew we had al the French Army against us, and if we could not maintain our ground until Bulow’s corps arrived on our left, we had nothing but a retreat on bad roads, before a victorious enemy in view. Though no-one desponded, nothing could exceed the anxiety with which we looked to the height opposite Ohain for the Prussians; at last the French Vedettes on their right began to caper, cavalry skirmishing began, columns began to appear. (It was Blue Beard exactly:- I see them galloping.)Up came a gun, began to fire – soon another _ and another – French answering them, tirailleurs on both sides, but the Prussian right which appuyed on our left, nearly at right angles, but separated by the Ohain valley, remained stationary, and disappointed me rather; but I soon saw what they were at and it was a beautiful sight to see them bringing forward their left, as it formed up on their right, as a pivot; and to see the cannonade and fire run on, quite in the rear of the French, before this though it was rather alarming to have to look over one’s right shoulder, to our right, showing that it had fallen back, so that the battle had assumed the following form:-

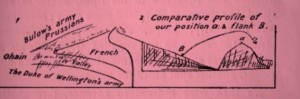

|

No.1 shows the general form of the action, as it appeared to me then, but I cannot attempt to give a plan of the ground. Our line was on rising ground, rising opposite, but like a glacis, more so that we could see over the whole of it. The ground was wheat and other cornfields in the morning, but by the movement of troops had become a complete and muddy squash, which saved many lives, as shots generally buried, unless they struck very obliquely: and shells buried so much that they were scarce to be feared at 20 to 30 yards distance if they had pitched, though both knocked up the mud finely. The roar of artillery was incessant, only varied by the report of some of our own guns, that happened to be near, an occasional shell bursting near, or the sound of shot.

At length we made a move to the right, in columns of half Squadrons, made a flank movement to the rear, in column, passed though a coppice, this was admirably done by General Vivian, as he kept us out of cannonade during this movement as long as he could, then on emerging from the coppice, got into a very heavy fire of musketry and artillery – passed by the then miserable-looking remnant of the Heavy brigade, crossed the Great Road – the great bone of contention – wheeled into line in rear of some infantry one, I believe, a battalion of Hanoverians, in red, one a battalion of Brunswickers, in black – these were falling back, and the French were advancing, so that I saw their Tirailleurs about 50 yards off. The battalion in black seemed in doubt whether they should retire through our intervals or not; indeed they were almost between two squadrons, part of them firing. We were ordered to advance, which we did, and these two battalions advanced close before us, their drums beating. Hereabouts, Colonel Quinton was wounded, shot through the ankle, and though he took little notice of it at first, was obliged to quit the field. Lord R. Manners then commanded.

We then wheeled half squadron to the right, went on some way, made a flank movement to the rear, by a large house, and movement to the front again, wheeled into line: here, in a short time, Captains Grey and Wood were wounded by musket shot, Captain Gurwood, commanding my right half squadron, was wounded. Grey’s horse had been wounded before, and was killed as he went to the rear, so was Gurwood’s: wheeled half squadron to the right, advanced, and stood in column, close behind some guns: here there was musketry, grape, and everything pleasant. Lieut. Hodgson, who had supplied Gurwood’s place, had his horse shot, close to me, before he could dismount, another shot killed the horse.

We were then ordered to advance, through the guns; just as my right half squadron had got exactly in front of a nine pounder, the man had the portfire in his hand to fire. I roared at him not to fire, he begged us to clear the gun ordered the half squadron to rein back, and the man fired so that the shot must have passed within two feet of their noses, and the blast quite shook them. We then advanced in column, and were ordered to gallop. Our right column, which had been separated by the guns, came up into its place, at speed we went over a rising ground, saw the French army going up, on opposite rising ground, our infantry advancing against them, on the left of us. In front of our column, they had infantry formed on the slope of the hill, and Cavalry, Lancers, Dragoons, and Cuirassiers behind them.

Just here Lord Uxbridge was wounded by a grape shot, advancing with our Brigade.

General Vivian gave the order:- “Front form the line and charge.”

The right Squadron was going so fast, we could not catch them, charged in echelon of Squadrons. As the right Squadron was going down with a grand “hussa”, which we all gave, answered by the Infantry, a division, or half squadron, of the 23rd Dragoons or 1st German Dragoons pushed on rather before our right. The Lancer, which were formed, charged down into the hollow on them, very prettily, and sent them to the right about. Our right Squadron, then commanded by Lieut. Arnold, after Captain Grey’s wound, came upon them, and drove them. Then, down came some heavy cavalry, in helmets, on the right squadron. The centre, my squadron, came upon them, and drove them. Soon after the order “front form the line” Lieut. Gunning, commanding my left half Squadron, – a very fine young man, – fell dead, shot through the heart, as the Infantry on the hill, and guns were firing at us. The left Squadron, under Major Howard, (a son of Lord Carlisle’s, and one of the most perfect gentlemen and best young men I ever knew.) was ordered by General Vivian to attack a hollow square of Infantry, at the same time with a corps of our Infantry, which was advancing upon it, and towards it.

Howard did not wait for the Infantry to attack, but charged, and the square was broken; many cut down and made prisoners, and a General taken, but poor Howard fell, with three wounds, and our men say, after he fell, a man stopped from the ranks and beat him on the head, with the butt of his musquet, Arnold, who commanded the near Squadron, was also shot through the lungs, and another shot through his arm, and Lieut. Bacon was shot through the thigh. I followed Lord Robert Manners with as many of the Squadron as we could collect, up a hill, where there were guns left and Infantry running away, and roaring for quarter. As soon as we came over the brow of the hill, we found a front of Infantry formed, with Cavalry in the rear about 35 yards off, who opened a sharpish fire on us. Lord Robert just halted us to get in order, and then gave a “hurra” and we went at them as hard as we could; they went about, horse and foot, and as we rode in amongst them, threw away their arms – threw themselves down, or off their horses – anything to save their bacon. We soon came to the brow of the hill, with a steep dip and a knowl opposite: here was a hollow square well formed, and very steady. Lord Robert halted to form our men again. Meantime, a party of the 18th, with Grant at the head, (brother of Brigade-Major that flirted with Miss Crommelin.) passed, dashed down the hill, and up the other side, at the square, and was, as I foresaw, repulsed, but it was done in gallant style indeed; nothing could be more gallant than the 18th, but wild enough of course. Having few men left together, and the rest of the Light Cavalry being coming up on all sides, we retired collecting our men, our horses many of them, (mine among the number) so done we could just make a walk, and having collected all we could then ,of three good squadrons formed two weak squadrons, and told them off. It was now dusk, and we could see the fuzzes of shells very plain; while we were telling off one fell very near us and burst. They say it came from the Prussians, the greater part of whom, being fresh, advanced, and pursued all night: as we had driven in the French right, and we were their left centre, they crossed us in pursuing, and some of them were near being cut down by our men.

When we were formed, we were ordered to advance a little, and to form of the brow of a hill; on the way we met lots of prisoners coming back, – some shouting “Vive le Roy” – (beasts), some “Vive l’Empereur”.

General Vivian came up to us, halted us and addressed us, saying the Regiment had completely fulfilled his expectations, and done everything he could wish, and “that he should take care that our Prince should know it.” The men gave 6 cheers: this certainly was a gratifying sensation.

We met other troops on the hill, where we halted and dismounted. General Grant, of the other Hussars Brigade, there met us, and said he had had 4 horses shot under him that day. We saw great fires marking the retreat of the French. They had left about 160 pieces of canon in our lines, and that night the Prussians took about 60 more, with all their baggage, and Buonaparte’s coach, with the door open, and everything left in it – orders of different nations, a library, proclamations read printed, dated at a place near Brussels.

It was now moonlight, near 10 o’clock, when we marched about half a mile to a wheat field, dismounted and linked horses, got some cold meat out of a haversack, some beer from a farmhouse, and my pipe, the greatest comfort possible; then laid down with a thankful heart for having come safe and sound out of such a dreadful carnage (neither self or horse had one touch) and had a capital sleep until day-break, which the transactions of the last three days had rendered rather necessary.

Next morning (19th) the 18th and 10th – now 4 weak instead of 6 strong squadrons – marched half a mile to feed, in a clover field, and we got some breakfast in a farmhouse, which had many wounded French in it.

Here I wrote to Anne, and sent the letter off.

Colonel Canning, A. D. C. to the Duke of Wellington, who had been desired by a friend of Anne’s to give an account of me after any general action, had been killed by a canon shot.

We sent a party to bury our dead, and to try and find Major Howard, but they could discover nothing of him; it appears since that he was buried by a sergeant and man, who are now gone back to take up the body. He was shot in the head and the body and his wrist broke. By their account, Gunning had been buried before.

I wish I had gone over the ground, to have formed some idea of where we charged and pursued, but had no time.

|

The Buony had had built to command the whole from.

About 12 we marched to Hautaine de Mont, near Nivelles.

20th through Nivelles and Binche to Merbe St Marie. Here they told us that the fugitives swore “Leipsic was nothing to the 18th”

21st to Bettignier, near Malplaquet.

22nd from Bettignier, through Coteau Cambrein, to St. Brenin, a long march.

23rd halt, Cambray attacked, hear the firing.

24th halt. Hear Buony’s abdication. Cambray taken.

25th to Cricourt, near St Quintin. Here I must tell you, the master of a good house we were quartered in said “That a Colonel of French Chasseurs retiring, had said that a Regiment of English Hussars, followed by another Regiment of cavalry, had made a charge that completed their rout.”

I had heard this once before, and it shows that General Vivian was not far wrong. He told us in his address after the action “that our charge had decided the business,” which I , being a moderate man, attributed to a little enthusiasm of the moment, but both that report, that I heard twice, and Buony’s despatches show that there was some reason for it. The Duke’s despatch, to be sure, takes no notice of the charge of the Hussars brigade at all, any more than saying, that the cavalry advanced, but as is usually the case with him, whether from the love of conciseness or a wish to avoid the other extreme, which is very absurd and much worse, he certainly is rather dry in his despatch; but he has felt warmly shed tears for many that had fallen, and in private letters, has written most warmly. It is better as it is perhaps, but one would think that charging and breaking squares of Infantry, deserves some notice, as well as the conduct of the heavy cavalry in the centre, which I believe, was highly to their credit.

Sir W. Ponsonby’s Brigade charged, and completely routed, and cut up, a large column of Infantry.

The Blues and Life Guards knocked the Cuirassiers Infantry about a good deal, and Buonaparte speaks more than the Duke for them, showing the loss they occasioned him, and the confusion amongst his batteries.

The Heavy Brigade, having broken the Infantry, where for going to Paris straight, nothing could stop them. The consequence was, of course, their suffering severely in the end, and poor Sir W. Ponsonby was killed. The Greys buries 8 Officers, but the end was answered.

The French was kept exposed to terrible fire, much cut up, and prevented from doing anything, and you may depend on it, the French had nearly double to number of cavalry in the field that we had. As for any, except the British and German Legion, they might as well have been anywhere else; for the Cumberland Hussars, a Hanoverian Regiment – fine men and horses and well appointed – bolted coolly, in the best order possible the Colonel saying “his men were unaccustomed to fire”. He is in arrest, I believe. The Duke sent to beg he would stay anywhere in moderate distance, but in vain. As for the Infantry, one need say nothing of them; nothing could excel their firmness and gallant conduct; nothing could shake them; I mean the British. And the Hanovers and Brunswicks behaved well, not all the Belge, but I say so much about the cavalry – because with that prejudice which the Infantry very liberally keep up against the Cavalry – many I hear it said, do not scruple to hear it say, the Cavalry did nothing (vide Buonaparte’s dispatch, say I.) This is not the general opinion though, but if one man writes it to England, and another sends an extract of his letter to India, the Calcutta story will be the Cavalry all run away. I believe you know my adverse to exaggeration, and fond of truth, therefore I tell you so circumstantially what I saw myself.

I cannot conceive anything superior to the steadiness of our Regiment. Marching in column of half Squadrons interval preserved under fire, 3’s about retiring, halting, fronting, as steady as at a field day. Gen. Vivian speaks of it in the highest terms.

The French Cuirassiers could not stand our heavy Cavalry, but they must have an advantage, only arms, face and thighs that can be hurt, except by canon. I have a Cuirass by way of trophy, with its backpiece. Grapeshot has gone right through the belly part, but the back has a dent of musketry shot in it, not gone through. The Lancers have in a front charge an advantage, and I think are formidable, particularly along a road, but if you can outflank and break them they are helpless. They are great beasts, and most of our Officers were piked by them, they piked the wounded on the ground. I, therefore, recommend them particularly to the attention of our men. The 7th, they say, got a number of them into a wood, with an abbatis at the end, and paid them well. Sir W. Ponsonby was speared by them, Major Pack of the Blues, ditto, Captain Thoits of the Blues wounded, but he parried the lance: however, he was surrounded, and taken to Buonaparte, who asked him questions He got off in the pursuit.

Col. Ponsonby’s[i] (of the 12th Dragoons) is such a serious history I must tell it. He charged with the 12th, who drove back the enemy, but would not halt; were attacked and overpowered in turn; he had his bridle arm disabled by a cut, then the sword arm, then a cut on his cap on the forehead, that felled him: as he lay under the enemy and his own men fighting, a horse stepped on his face that stunned him. When he came to himself he heard a horse near him, saw a Lancer, and said he was a English Officer wounded, and asked for assistance, of course considering himself a prisoner. The Lancer said, with some abuse “Vous n’êtes pas encore mort” and run his lance through his body. This rendered him insensible again. When he was next recovered he found himself stripped, and piled up with the dead bodies, making a kind of parapet, from behind which a Frenchman was loading and firing, close to him, as hard as he could, and canon were firing so close as to shake the ground near him every time. The shot from our own guns also pitched thick about him. He spoke to the Frenchman who, however, went on with his business at last said “Well, I am off, things go ill for us; bon soir.”

After this, on our troops advancing, a man from the 40th came looking about this heap of bodies, to see what was to be got. Col. Ponsonby could not speak loud enough to make him hear, but on his coming near, took an opportunity to seize his arm, and getting his ear near his mouth, told him who he was, and begged him to stay near him until next morning, and he should be rewarded. The man hesitated, but being at last persuaded that he was an English Officer, disclaimed any reward, but stayed with him. Next morning, young Vandeleur of the 12th, going over the field, found Col. P and the man by him. He was taken to Brussels and is now doing well.

There are no doubt many adventures equally curious.

On the 16th, an Officer of the Guards, wounded and taken, was being conducted to the rear: he heard the men who were guarding him, coolly talking of cutting his throat; he met a French officer, told him this, and threw himself on his protection. The French officer gave him in charge to another, who asked him, when they were alone “Whether he chose to go see his friends?” He said “certainly, if he could.” The other, a German, said he meant to do the same thing, told him to go through the corn and meet him at the corner of the field. They met there, and the Officer showed him the road to Nivelles and wished him a good journey. He got to a farmhouse and got carried to Nivelles in a cart.

Ann officer of the name of Colquhitt of the Guards took up a shell and carried it out of a square.

The Duke of W was much exposed the whole time, once seeing a Battalion falling back, he said “Oh, they are coming in are they; I will soon remedy that.” He went and cheered them on, hat in hand, and set all to rights directly. He says “He never saw such fighting before, and hopes he never shall again.”

Buonaparte exposed himself too much, and made great exertions. Ney accused him of bad management, and says he kept a corps of reserves useless, and doing nothing be fatiguing themselves, with marching from right to left, left to right, from want of decision where to employ them.

Besides those returned wounded in our Regiment, the Adjutant had several balls in his cloak which he had on, and one violent contusion in the ribs, from a musquet ball. Lord Robert was wounded in the shoulder with a pike or sward. He did not know it, but I found it out when he first undressed. There was a good deal of blood, and a hole through waistcoat and jacket, with a slight puncture.

Lt. Hodgson got a good sliver on the cap, and a cut on the hand. A fellow hit my shoulder without cutting me however, and a good “right protect” saved my nose from a considerable sliver, if I may judge from the notch in the sword.

We had only thirteen men killed, about 35 wounded, a very small proportion considering that 2 Officers were killed and six wounded out of 16. 40 horses were killed and about 40 wounded, many in two or three places.

Now to return to my digression —- a pretty long 25th June to Mattignies near the Lomme. A patrol of ours under Lt. Smith brought in Count Lauriston.

27th. To Vespilly; 28th to Autheuil; 29th across the Ouse at Pointe St. Maxeme, to Senlis; 30th to Vandellan, bivouac in valley. Quite curious to see the destruction of the villages by the Prussians, who had kept the start they got the first night.

1st July halt at Vandellan, but at 9 at night had an order to march; after about six miles halt and dismount, and lay down to sleep; 2nd, in morning being near Mont Martre, thought we were going to have a general action; move into bivouac to the right of Bourget; live in a hut of boughs of my own building. Heavy cannonade the other side of Paris in the day, being, as we learnt afterwards, a sharp action between Blücher and the French, begun at St. Cloud, and ending in Paris. He lost 3,000 men, but gave the French such a licking, they asked for an armistice.

So on the 3rd, going on picquet with a squadron, in front of the French posts, under Belleville, I received orders for my ~Vedettes not to fire, or to commit any hostilities.

4th, Bob Elliot joined me in bivouac, and enlisted with the Tenth for the campaign – the convention for the surrender of Paris announced.

5th, part of my baggage which had never appeared (any of it) since the 16th June, unexpectedly re-joined me. It was found by a Belgic Countess, near her chateau, and being directed, she took it to Brussels and gave it to the Paymaster of our Regiment, who brought it on.

6th, Capt. arrives at N. Q. of the guards.

7th March round Paris by a pontoon bridge at Argenteuil, to this place, where I have good quarters at a gentleman’s house on the banks of the Seine, where I have been ever since but two picquets of the Regiment, in the Champs Elysees.

I have admired the Louvre, St. Cloud, and Versailles, and been keenly received by a French Family, friends of Anne’s. Bob Elliot still with me.

Paris seems very quiet, and the King goes down well enough, but to know the real sentiments of these weathercocks is out of the books. This is a long epistle, but I remember how interesting any account of an eyewitness was in India. I wish you let Fergusson see it, and George Norris, whose brother, by the bye, is appointed Judge-Advocate to the Army, and is coming out directly. I congratulate you on the birth of the young one, and Elizabeth’s safety, my kind love to her.

I should, perhaps, have written to Fergusson, id I had been sure of his being in India.

Believe me, dear Brownrigg,

Yours ever sincerely

- W. Taylor.

You seem to be getting up a row in India to pass the time.

Yours T. W. T.

Bob Elliot begs to be remembered to you and Mrs B. Of course, give my kind love to Fergusson and Peggy, if this finds them in India. I should tell you, as you will rejoice in my prospects, that the senior Captain, Bromley, not having served his time, I am likely to succeed to the majority, good for me though I lament the cause, God knows, most sincerely. I am recommended to the brevet rank of Lieut.-Colonel. If I get one of them I shall have no cause to complain. I do not see much of Capt. Elliot; He is with Capt. Bowles, and they are seeing all they can. I am confined in some degree. The French puff and praise us, for using them so much better than the Prussians. Old Blucher was going to blow up the Pont-de-Jena – a beautiful bridge, but it is now to be spared, but its name changed. All pictures and statues are to be sent back to their owners. In short I trust this nation will remember that it has been conquered.

Not that I consider the nation and the army as the same, tho’ had the army been successful, and got possession of Brussels, the nation would, no doubt, had been all ready to support it, and have shouted vive Napoleon as loud as ever.

[i] Colonel Ponsonby was originally a Tenth Hussar – a brief summary of his services is given in the Regimental Memoirs, published in this Gazette